Water is a basic human need — without it, survival beyond a few days is impossible. While staying hydrated may seem relatively simple, there are a lot of factors at play that can influence hydration. Read on to find out more about the 411 on the H2O.

So — what’s it good for?

At birth, humans are about 75-85% water by weight, which decreases to about 60-70% in adulthood. This water does more than just contribute to our gravitational pull; it makes itself useful by:

- Serving as a medium for cellular processes.

- Carrying oxygen and nutrients to cells.

- Carrying wastes to the liver and kidneys for excretion.

- Producing sweat, which helps to regulate body temperature by cooling the blood vessels below the skin.

How much fluid do I need to drink every day?

Simply put: fluid intake must replace output in order to prevent dehydration.

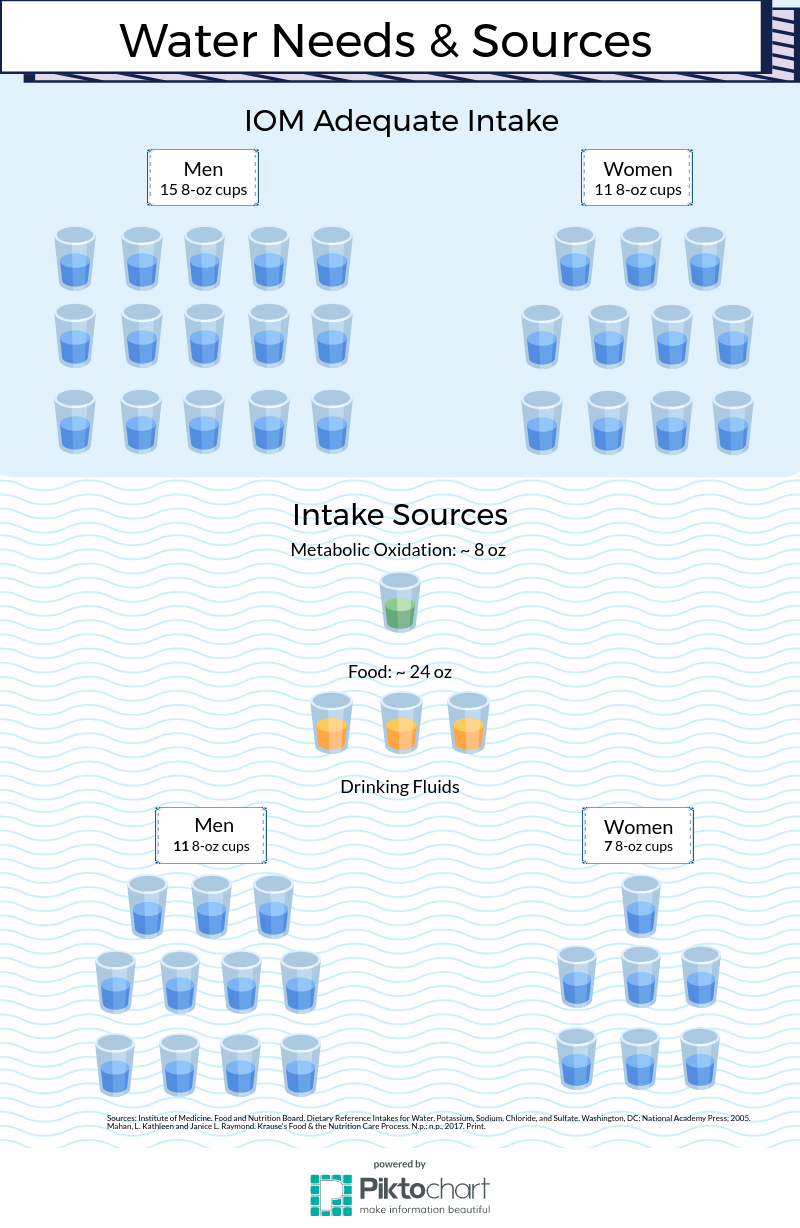

Obvious sources of water loss include urine and feces; an additional ~0.8-1.4 L of water is lost per day via “insensible” avenues (sweat & exhaling) (1). For most adults, a suitable daily water intake to replace these losses (the Adequate Intake (AI) from the Institute of Medicine) is as follows (2):

- Men: 3.7 L/day (15 8-oz cups)

- Women: 2.7 L/day (11 8-oz cups)

Fluid needs can also be estimated based on kilograms (1):

- Adults: 35 ml/kg

- Children: 50-60 ml/kg

- Infants: 150 ml/kg (higher needs due to higher body water content and kidneys with a lower ability to handle a high renal solute load)

We may have higher water needs in conditions promoting high fluid output, such as:

- A hot environment (increased sweating)

- Heavy exercise (increased sweating)

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

On the flip side, the body may retain fluid because of physiological stress or compromised liver, kidney, or cardiac function, which may consequently require fluid restriction (the amount is usually determined by a doctor). Thus, as with many aspects of nutrition, a once-size-fits-all approach is not the best venue — it’s best to look at the whole picture and individualize.

What are the best fluid sources?

While water is the best choice for rehydration in most cases, other fluids that can contribute to total body water content include juice, coffee, tea, sports drinks, and milk. Along with drinking fluids, about 200-300 ml of fluid are produced via cellular oxidation, and the water found in consumed foods typically constitutes roughly 19% of fluid intake (1). Altogether, these two sources comprise about four 8-oz cups of fluid. As shown by the graphic below, the remainder (eleven 8-oz cups for men and seven 8-oz cups for women) can be obtained via beverages.

How do I know if I’m drinking enough fluid?

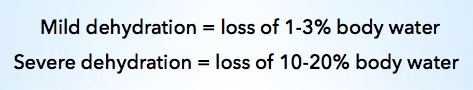

The simplest way to tell if you’re drinking enough water is to look at the color of your pee. If it is a light yellow color, you are drinking enough water. If it is darker (similar in appearance to apple juice), you need to drink up. Other symptoms of mild dehydration include headaches, dizziness, sleepiness, and difficulty concentrating.

What about coffee?

Contrary to popular belief, coffee does not lead to dehydration. Coffee earned this reputation from findings of a study performed in 1928, which showed that people who consumed caffeine had an increased urine output (3). Studies since then have shown that while coffee does appear to have a mild diuretic effect, total body water volume doesn’t decrease as a result (4-8). Additionally, as you’ve probably experienced first-hand, drinking any fluid (including water) will increase urinary output; it’s just a matter of making sure that output is adequately replaced.

What about exercise?

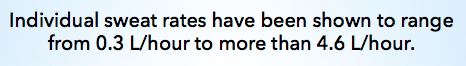

Water intake before, during, and after exercise is important, as a loss of 1% to 3% of body weight via fluid can lead to decreased athletic performance, concentration, and short-term memory and increased moodiness and anxiety (9-14). Sweat loss varies depending on the climate, acclimation to heat, clothing, and equipment, highlighting the importance of individualizing intake needs.

Water needs for exercise for adults are as follows (15):

- Two hours before: 16-20 oz

- During: ~16 oz every 15 minutes; add electrolytes if >2 hours or large sweat losses

- After: 20-24 oz per pound of body weight lost or 1.5 L for each kg body weight lost

In addition to water, electrolytes are also lost via sweat and thus require replacement. However, water is usually adequate to rehydrate after exercise lasting one hour or less, unless if a person has an unusually high sweat rate or is exercising in a very hot environment.

The main electrolyte lost in sweat is sodium. Losses are difficult to estimate, as they vary from person to person (see the table below) (9). Excessive sodium loss can put one at risk for muscle cramping as well as decreased athletic performance. Rehydrating with inadequate sodium can dilute blood sodium levels, which in extreme cases can lead to brain swelling, coma, and death. Other electrolytes lost via sweat are chloride, potassium, calcium, and magnesium (9).

|

Estimated Electrolyte Losses in Sweat (9) | |

| Electrolyte |

Estimated Range (mg/L) |

| Sodium | 230-2277 |

| Chloride | Lost along with sodium |

| Potassium | 78-390 |

| Calcium | 6-10 |

| Magnesium | 2.5-18.5 |

As previously stated, water is adequate to rehydrate after exercise lasting one hour or less. Beyond this, replacement of sodium must occur along with rehydration.

Typical venues that are adequate for replacing fluid and sodium sweat losses include:

- Sports drinks (Gatorade or Powerade)

- Water along with sodium-rich foods (some examples: cottage cheese, pretzels, pickles, salted nuts, chicken breast, cheese, canned tuna)

Other less popular options:

- Oral rehydration beverages (Dioralyte or Pedialyte)

- Pickle juice

- Milk

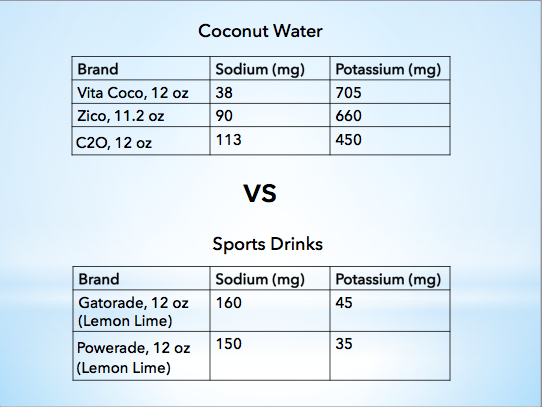

Coconut water is not the best option for rehydrating after excessive sweating, as it contains a lot of potassium but little sodium, as shown in the tables below.

Zico: http://www.coca-colaproductfacts.com/en/products/zico/

C2O: http://c2o-cocowater.com

Gatorade: http://www.pepsicobeveragefacts.com/Home/product?formula=33877&form=RTD&size=20

Powerade: http://www.coca-colaproductfacts.com/en/products/powerade-lemonlime/

Potassium generally does not need to be replaced after exercise (another reason why coconut water is not the best rehydration drink). Similarly, calcium and magnesium replacement is usually unnecessary, as these electrolytes are lost in small amounts and are redistributed in the body as needed for metabolic processes. Adequate amounts of these electrolytes should be achieved via a balanced diet (2,9).

Tips for getting enough water:

- Buy a reusable water bottle to refill throughout the day.

- Don’t like plain water? Try flavoring it with fresh fruit and herbs.

- Still don’t like it? Try out some seltzer water.

- Exercise regularly and wondering if you’re getting enough? Find a Registered Dietitian who can help you figure it out!

Sources:

- Mahan, L. Kathleen, and Janice L. Raymond. Krause’s Food & the Nutrition Care Process. N.p.: n.p., 2017. Print.

- Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2005.

- Eddy N, Downs A. Tolerance and cross-tolerance in the human subject to the diuretic effect of caffeine, theobromine and theophylline. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1928;33(2):167-174.

- Armstrong LE, Pumerantz AC, Roti MW, Judelson DA, Watson G, Dias JC, Sokmen B, Casa DJ, Maresh CM, Lieberman H, Kellogg M. Fluid, electrolyte, and renal indices of hydration during 11 days of controlled caffeine consumption.Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2005 Jun;15(3):252-65.

- Fiala KA, Casa DJ, Roti MW. Rehydration with a caffeinated beverage during the nonexercise periods of 3 consecutive days of 2-a-day practices. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004 Aug;14(4):419-29.

- Killer SC, Blannin AK, Jeukendrup AE. No Evidence of Dehydration with Moderate Daily Coffee Intake: A Counterbalanced Cross-Over Study in a Free-Living Population. Plos One. 2014 Jan 9;9(1):e84154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084154.

- Maughan RJ, Griffin J. Caffeine ingestion and fluid balance: a review. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2003;16:411-420. Doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00477.x

- Maughan R, Watson P, Cordery P, Walsh N, Oliver S, Dolci A, Rodriguez-Sanchez N, and Galloway S. A randomized trial to assess the potential of different beverages to affect hydration status: development of a beverage hydration index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(3):717-23. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.114769.

- American College of Sports Medicine, Sawka MN, Burke LM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and fluid replacement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(2):377-390.

- Osterberg KL, Horswill CA, Baker LB. Pregame urine specific gravity and fluid intake by National Basketball Association players during competition. J Athl Train. 2009;44(1):53-57.

- Montain SJ, Coyle EF. Influence of graded dehydration on hyperthermia and cardiovascular drift during exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1992;73(4):1340-1350.

- Adan A. Cognitive performance and dehydration. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012;31(2):382-388.

- Armstrong LE, Ganio MS, Casa DJ, et al. Mild dehydration affects mood in healthy young women. J Nutr. 2012;14(2):382-388.

- Ganio MS, Armstrong LE, Casa DJ, et al. Mild dehydration impairs cognitive performance and mood of men. Br J Nutr. 2011;106(10):1535-1543.

- Kundrat S, Rockwell M. Sports Dietetics: Practiced, Proven, and Tested Manual. Nutrition on the Move, Inc; 2008.

Pingback: Questions a Dietitian asks about Game of Thrones: Human Starvation & Refeeding Syndrome – Peace & Pancakes