Some food for thought: humans have succeeded at putting a man on the moon multiple times, explaining the physics of faraway stars and black holes, and figuring out how to access the internet in the palms of our hands. Yet, we still have not fully answered nutritional science questions such as: How do we most accurately predict energy needs? What is the optimum vitamin D intake level? What are the numerous factors that contribute to and treat chronic conditions like diabetes?

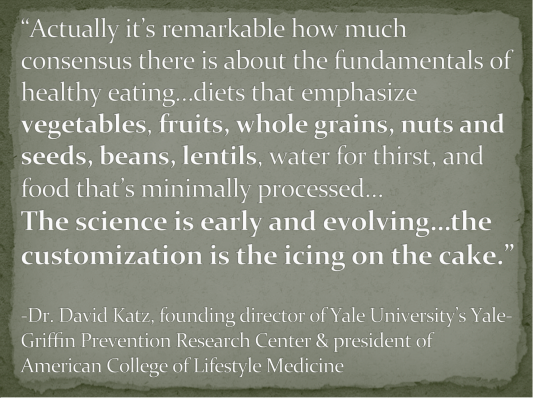

The fact that nutritional science is an ever-changing field with a lot of gray area is exciting and inspiring at times, but in the context of today’s world of information overload, it’s also the perfect storm of confusion and frustration. Information disseminated through social media, television, podcasts, and magazines often has truth and may even be supported by scientific research studies that are certainly important to consider. However, flashy headlines often cover only the tip of the iceberg and require further investigation prior to widespread application.

Learning how to write and evaluate scientific research articles was a vital part of my training to become a dietitian. Listed are some useful tips on assessing nutrition information, whether a scientific research article, magazine article, or social media post.

Multiple sources are better than one.

One basic principle of writing a scientific literature review: include a variety of sources. Literature reviews published in research journals often cite 50-100 scientific articles. The reason? Using a variety of sources assures reliability – the results are consistent and reproducible (or they aren’t).

In addition to reliability, including a variety of sources is also vital because it promotes a more balanced presentation of evidence. In the world of scientific literature reviews, authors do this by establishing inclusion criteria. After searching a database, all of the articles that fit these criteria must be included in the research review, no matter their findings. Thus, the author gives a more balanced review of the evidence, rather than just investigating findings that support one outcome.

In a nutshell, one blurb in a magazine about the positive outcomes of a certain diet, exercise regimen, or supplement is just a tiny piece of the puzzle. Seek out different viewpoints to see if the information checks out repeatedly, especially in cases where a plethora of information supports only one side of the story – which takes me to my next point.

Look out for bias.

While the bias in an extremely critical documentary may be blatantly obvious, it may not be as clear in other forms of information dissemination. Even the most well intentioned humans may allow their bias to impact how they present information, whether they want it to or not (another reason why it’s always good to follow tip #1).

An obvious red flag for bias is the funding source(s) and/or the author’s employer, such as a company that manufactures whey protein powder funding a study that concludes that whey protein is superior to soy protein in promoting muscle fiber recovery. Although this doesn’t completely dispute the findings, it may be worth investigating if the results were reproduced in other studies.

In addition to scientific research, other mainstream publications (including social media) can be influenced by investors or simply the desire to make money, both of which may cause the author to exaggerate information (whether intentionally or unintentionally) to prove a point. Once again, this doesn’t necessarily make the information invalid, but it does warrant more investigation.

Bias isn’t necessarily always a bad thing. It’s good to have strong convictions and stand up for what you believe in. However, a healthy dose of skepticism is helpful in coming to the most truthful conclusion, especially in a situation where an author may have an obvious reason for bias. A good way to combat bias is to consider varying viewpoints, as discussed in the next tip.

Investigate the information from all angles.

Scientific research articles usually include a limitations section, which describes flaws in the research or findings. After all, there’s still so much we don’t know, and we can’t control everything. Limitations could include:

- Confounding factors (variables other than those in question that may have influenced the findings)

- Flaws in methodology

- Lack of diversity in the sample population

- Human error

- The directionality of a correlation

Simply put: is it reproducible, can it be proven false, and are there alternate explanations?

Don’t be fooled by blanket statements.

Broad, lacking in sufficient supporting evidence, and often too good to be true, blanket statements thrive off of a lack of scientific understanding of nutrition and a desire for a “quick fix.” While there are endless examples to explore, let’s deconstruct one that is hot in today’s world of carbohydrate aversion: the assumption that a low-carb diet is superior for inducing weight loss because “carbohydrates make you gain weight.”

First and foremost, eating any food (not just carbohydrates) in excess may lead to weight gain. Additionally, “carbohydrates” is a broad term that describes a variety of foods. Those that are rich in fiber, vitamins, and minerals (such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains) are a beneficial and important component of the diet. In fact, these foods are associated with a reduced risk of developing, as well as improved management of, a variety of chronic health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

Of course, eating a diet rich in refined grain products (white bread, cereal, pastries, cookies) and sugary foods (soda, candy, ice cream) may promote weight gain as well as other adverse health outcomes; however, these foods can still be enjoyed as a component of a nutritious diet. It’s called moderation.

As the saying goes, if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. Take a step back to analyze if the claim truly checks out. (Read more about low-carb here and here).

Remember that statistical significance is not the same as clinical significance.

A research study is usually considered successful if it finds that a tested hypothesis is statistically significant, which means that the change or outcome observed is not due to chance. However, just because an observation is statistically significant does not always mean that it’s relevant to real-world practice.

The question of whether outcomes are clinically significant requires critical thinking, a basic understanding of research methods and statistics, and experience in the field at hand. Thus, be aware that statistically significant findings may be blown out of proportion to make a flashy headline; take the time to check the numbers and findings yourself, and consult experts in the field.

Two examples of how media headlines sometimes present research findings out of proportion to how they may appear practice are as follows:

- Studies that are performed using mice in an extremely controlled environment in which the amount of a food or nutrient administered is much larger than a human would ingest.

- Studies involving human participants in which the mode of administration of a food or nutrient may be very different than how it is typically consumed.

Studies that are constructed similar to those described above do produce meaningful findings in understanding nutrition. However, it’s important to remember tip #3. Limiting factors include that these studies are a) extremely controlled (and human behavior and physiology tends to have a lot of variation) and b) do not represent how humans actually consume a food or nutrient. Thus, I’ll say it again: further investigation is warranted.

Remember that correlation does not equal causation.

If there’s a correlation or association between two pieces of data, that doesn’t necessarily mean that one caused the other — the direction of the effect could go either way. The gold standard of research design, the randomized controlled trial, can indicate cause and effect. However, the majority of media reports covering new research discuss research designs that are observational in nature and thus can only point to correlation. Often, these media reports do not adequately distinguish the difference between correlation and causation.

For example, let’s say a study finds that participants’ increased water intake was correlated with increased sleep quality. Does this mean that increasing water consumption increases sleep quality, or improved sleep quality promotes water intake? If the study is observational in nature, there’s no way that we can prove either of those directions.

Additionally, there could be other confounding variables that influenced the main relationship observed. Perhaps people who sleep better are more focused on self-care and thus are more conscious of their water intake. Perhaps they exercise regularly, which influences both their sleep quality and water consumption. Once again, if the study is observational, we have no way of knowing if these or other factors are playing a role in the relationship at hand.

Correlations certainly point to healthy changes we can adopt, and single studies sometimes can be used right off the bat to provide guidance for lifestyle changes. However, widespread recommendations are usually based off of a critically examined body of evidence, as explained in the next point.

Anecdotal evidence is not the same as a large body of evidence.

Anecdotal evidence appears in scientific research in the form of case studies in which one or a few cases are presented, such as the management of an epileptic child on a ketogenic diet. In the world of the Internet and social media, this manifests in the form of personal blogs and before-and-after Instagram posts advocating for a certain food or exercise regimen because of personal success. In these cases, it’s important to keep in mind that while an intervention may have been successful for an individual, it is not necessarily the best route for everyone.

Consider: a lot of factors go into the treatment of diseases or conditions as well as outcomes such as weight loss, reduction of symptoms, and increased muscle mass. Nutrition is certainly an important piece of the pie, but humans are not robots; our bodies and health are influenced by genes, hormones, stress, sleep, socioeconomic status, education level, psychology, and activity level (just to name a few factors). Making recommendations that aren’t strongly supported by scientific evidence could result in positive outcomes but could also be detrimental or simply have no meaningful impact. This is why dietitians are trained to provide evidence-based practice, especially in high-risk populations where a detrimental outcome could prove to be especially devastating.

Once again, emerging research studies and success testimonials certainly point to worthwhile interventions we can use as guidance and inspiration. However, inspiration aside, don’t assume that these interventions will work well for everyone or that they are necessarily best route to take in terms of health and longevity.

Accept the fact that with nutrition, the answer is often “we’re not sure yet.”

After studying nutritional science for only five years, I’ve already realized that it’s still a baby science – there’s so much we don’t know. It’s important to keep in mind that, as previously stated, humans are not robots. Our bodies do not always function in a predictable manner, and we still have a lot of ground to cover on understanding our own biology and physiology. Thus, claiming that any one food or nutrient is the solution to or the cause for all of humanity’s health problems is just silly.

Of course, nutrition research sometimes takes time to catch up to the truth, and scientists have proven they can be wrong again and again. Thus, let new information guide your nutrition knowledge and decisions, and remember that it might not be set in stone just yet. If you feel confused, know that you’re not alone.

Keep it simple.

Truthfully, the core components of a balanced diet haven’t changed much. If you ever feel lost amongst the sea of abundant nutrition information, you can always come back to this:

- Eat a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, & lean proteins.

- Decrease intake of refined grains, added sugar, and saturated fat.

- Don’t go too long without eating (3-5 hours).

- Drink water.

- Eat when you’re hungry, stop when you’re full.

- Know that it’s okay to eat for reasons other than hunger, and it’s also okay to eat beyond fullness. Remember: you are not a robot.

- Enjoy your food!

Pingback: To Try or Not to Try: Atkins – Peace & Pancakes